AI Lawyer Blog

Personal Loan Agreement Template: U.S. Terms, Clauses & Forms

Greg Mitchell | Legal consultant at AI Lawyer

3

Lending money to a friend or relative usually starts casually: “No rush, just pay me back.” The trouble is that a verbal deal is easy to reinterpret once time passes, finances change, or a payment is missed. One person remembers a flexible timeline; the other expects a monthly payment. Someone assumes the transfer was a loan; the other treats it like help. That’s how small misunderstandings become big relationship problems.

A personal lending agreement doesn’t need to be complicated to be useful. A clear individual loan agreement turns vague expectations into specific, dated commitments: how much was loaned, when repayment starts, what counts as “late,” and what happens if someone can’t pay on time. When you write those terms down, you protect both sides, not just the lender.

In this guide, you’ll learn how private, person-to-person loans are typically documented in the U.S., and how to choose between a full agreement, a simpler note, or a minimal acknowledgment. By the end, you should be able to pick the right personal loan contract for your situation and avoid common enforceability gaps. For best results, read in order: first understand which document fits your deal, then review the key terms you must define, then use the scenario-based templates and the step-by-step filling process.

Disclaimer

This guide provides general information about a personal loan agreement and is not legal advice. State laws and outcomes vary, and your facts (amount, interest, repayment structure, collateral) can change what terms are appropriate. A written personal loan contract can prevent misunderstandings by making the deal measurable and enforceable, but it may not address every state-specific requirement or special situation. If the stakes are high (large amounts, collateral, co-signers, or multi-state issues), having a U.S. lawyer review the document can reduce costly mistakes before anyone signs.

TL;DR

A personal loan agreement is a written contract that spells out repayment terms so neither side has to rely on memory. It’s especially helpful when money and relationships overlap.

Use a written agreement when the amount is meaningful, repayment stretches over time, or you expect partial payments. The longer the timeline, the more a clear schedule matters.

The “must-have” terms are the amount, disbursement date, repayment schedule, interest (or no interest), late fees, default triggers, and how notices are delivered. If any of those are vague, enforcement gets harder.

A loan agreement is usually the most complete option, while a promissory note is a simpler promise to pay and an IOU is typically just an acknowledgment. If you want real protections (default remedies, notice rules), choose the fuller document.

Secured vs unsecured changes the risk: secured loans use collateral, unsecured loans rely on strong payment terms and proof. Collateral must be described clearly and released when paid off.

Friends and family loans work best when boundaries are explicit and records are easy to keep. Clear terms can reduce resentment more than they create “awkwardness.”

After signing, tracking payments is what keeps the agreement real. Keep a payment log (date, amount, method, memo, remaining balance) and save proof of each payment.

You Might Also Like:

What Is a Personal Loan Agreement?

Definition (plain English)

A personal loan agreement is a written contract where one person lends money to another and both agree — up front — on repayment terms. In everyday terms, it turns “I’ll pay you back” into specific, dated obligations that are easier to prove and enforce if there’s ever a disagreement. If you want a high-level refresher on what makes contracts enforceable, see Cornell Law School’s overview of contract law concepts.

What it covers

A solid personal loan contract covers two buckets: the money terms and the “what happens if…” terms. The goal is to make the loan measurable (numbers and dates) and workable (clear rules if a payment is late). In most cases, that means: who the parties are and where notices go; principal and disbursement method/date; interest (or a clear no-interest statement); a repayment schedule; what counts as “late” and any grace/late fee; default triggers and next steps; and signatures.

Because people want a stable record, it’s common to save a signed final version as a PDF, but the format matters less than whether the terms are complete and consistent.

What it doesn’t solve (state-specific + special cases)

A template can’t automatically handle every state rule or unusual fact pattern. State laws may affect issues like maximum interest (usury), required wording for certain remedies, or how collateral should be documented. Taxes can also matter (especially for interest-free or below-market family loans), and the agreement itself doesn’t guarantee payment — it mainly improves clarity and enforcement options if things break down.

When Do You Need a Personal Loan Agreement?

A personal loan contract is most useful when time and expectations can drift. As soon as the loan is “meaningful” to either person, repayment stretches beyond a few weeks, or you plan to accept partial payments, putting the deal in writing prevents the most common misunderstandings.

You should also document the loan when the terms have any complexity: you’re charging interest (or you want it clearly interest-free), you’re using collateral, a co-signer is involved, or you want defined late fees and default rules. In a personal loan contract between friends, clarity is not about distrust — it’s about protecting the relationship with objective dates and amounts. Even a well-written loan agreement between friends can feel “simple” in practice if it’s short, specific, and easy to follow.

When a simpler document might work (and risks)

If the loan is small, paid back in one lump sum soon, and there’s no interest, collateral, or special protections, a simpler document may be workable. People sometimes start from a loan agreement sample or a very short sample loan agreement template and keep it minimal.

The risk is that minimal paperwork often skips the exact points that cause conflict: what “late” means, whether there’s a grace period, how changes must be made, and what happens if payments stop. The simpler the document, the more you rely on assumptions — and assumptions are where friends-and-family loans break.

If you want to start fast, use the general Personal Loan Agreement Template as a baseline, or use AI Lawyer to generate a first draft from your scenario — then keep reading for templates tailored to specific loan setups (family loans, loans between friends, unsecured installment plans, secured collateral loans, interest-free loans, demand loans, promissory note scenarios, and guarantor/co-signer situations).

Personal Loan Agreement vs Promissory Note vs IOU

Loan agreement (full contract)

A loan agreement is the most complete option because it sets out both the money terms and the “what happens if…” terms. It typically covers repayment structure, interest (or no interest), late fees, default triggers, notice rules, governing law, and any collateral or guarantor provisions. Use this when you want the relationship to stay calm even if circumstances change, because the plan is written down and measurable.

Promissory note (promise to pay)

A promissory note is a written promise by the borrower to repay a specific amount under stated terms. It can be perfectly valid and is often shorter than a full agreement, but it usually includes fewer “process” protections (like detailed notices, dispute options, or tailored remedies). It’s a good fit for straightforward loans with a clear due date (or simple installments) where you still want something more formal than a casual note. In many personal loan promissory note setups, the note is the core document, and any extra protections are added only if needed.

IOU (minimal acknowledgment)

An IOU is usually just an acknowledgment that a debt exists, often with minimal detail. It can be useful for very small, informal situations, but it’s the easiest to misunderstand later because it may not define repayment timing, interest, late fees, or what counts as default. If you’re tempted to use an IOU, the safest upgrade is to at least include the amount, date, and a clear due date — otherwise it’s closer to a memory aid than an enforceable deal.

Comparison table

Document | Best for | What it usually includes | Biggest risk |

|---|---|---|---|

Loan agreement | Situations where you need clear rules that prevent disputes and support enforcement. | Parties, principal, disbursement, interest/no-interest, repayment schedule, late fees, default/acceleration, notices, governing law, signatures; can include collateral/guarantor add-ons. | Overkill for tiny loans; if you copy a template without tailoring, you can create gaps or inconsistent terms. |

Promissory note | A clear promise to repay with simpler terms and less “process.” | Principal, interest (if any), due date or basic schedule, payment method basics, signatures; sometimes limited default language. | Missing protections: fewer notice rules and remedies; may be too thin for complex or higher-risk loans. |

IOU | Very small, informal debts where both sides want a quick written record. | Amount owed, date, sometimes a due date; often minimal detail. | Too vague to manage late payments, interest, partial payments, or disputes — easy for each side to “remember” it differently. |

Pick in 30-second decision logic (in plain English)

If you mainly need a signed promise to repay a specific amount by a clear due date (or simple installments), use a promissory note.

If the debt is small and you only need a minimal written acknowledgment that money is owed, use an IOU — but it should still state the amount, date, and a firm due date.

If you need the document to handle friction (late fees, default steps, notice mechanics, collateral, or a co-signer), upgrade to a loan agreement because it spells out the “what happens if…” rules instead of leaving them to assumptions.

Personal Loan Agreement Format (Core Structure + Key Terms)

A strong personal loan agreement isn’t “more legal” — it’s more precise. The point is to force the deal into facts you can track: numbers, dates, triggers, and proof. Use the checklist below as your quality-control pass before anyone signs.

Core structure checklist (what must be defined)

Parties and notice addresses are stated clearly, including full legal names and at least one reliable notice address per side (mailing address, and optionally email). If this is incomplete, it becomes easier to dispute who is bound or claim notices were never properly delivered.

Loan amount and disbursement details are specific, stating the principal amount and how the money is delivered (wire/ACH/check/cash), plus the disbursement date and any reference number if available. If disbursement is vague, proving the loan was funded becomes harder.

Interest (or a clear “no interest” statement) is written, including the rate and how it accrues (simple vs other method) or a plain sentence that no interest is charged. If you leave this implied, payoff math and “what’s owed” can turn into an argument.

Repayment schedule is measurable, listing exact due dates and exact amounts (or one clear lump-sum due date), and clarifying whether payment counts when received or when sent. If the schedule is not measurable, “late” becomes subjective.

Payment method and proof expectations are defined, stating acceptable payment methods (ACH, check, etc.) and what counts as proof (bank confirmation, check image, signed receipt). If proof is undefined, both sides can struggle to reconstruct the payment history.

Late payment rule is objective, including the grace period (if any), the late fee (or an explicit “no late fee”), and when a payment becomes late. If the trigger is unclear, enforcement feels arbitrary and relationship tension rises.

Default trigger and next steps are written, defining default (missed payment, breach of collateral terms, etc.), whether there is a cure period, and what notice is required before consequences apply. If default is fuzzy, escalation is improvised and easier to dispute.

Acceleration (if used) is clearly described, stating whether the lender can demand the remaining balance after default and what notice must be given first. If acceleration is ambiguous, the borrower may challenge a payoff demand.

Prepayment terms are stated, clarifying whether early payoff is allowed and whether there is any penalty (often none). If omitted, early payoff can still produce conflict about interest or timing.

Collateral terms (secured loans only) are identifiable and precise, describing one specific asset with unique identifiers (VIN/serial number, make/model), location, and condition if relevant. If the collateral is described as a category, the “secured” protection may be weak in practice.

Release-on-payoff mechanics are included for secured loans, stating what the lender will deliver when paid in full (release confirmation, return of title documents if applicable) and the timing. If this is missing, the borrower can end up “paid off” but still stuck with unclear collateral status.

Guarantor/co-signer terms (if used) define scope and release, stating what the guarantor covers, when the guarantor can be pursued, and how/when the guarantor is released. If scope is vague, you create surprise liability and disputes.

Governing law and dispute options are consistent, naming the governing state law and, if included, the forum or dispute process. If this is inconsistent or missing, the parties may assume different rules apply.

Amendments must be in writing, stating that changes to dates, amounts, or schedule are valid only if written and signed by both sides. If you allow informal changes, the agreement tends to drift into “we agreed verbally” conflict.

Signatures, dates, and attachments are complete, including signature blocks, execution date, and any attached schedule or collateral description referenced in the text. If attachments are missing, critical terms can end up “outside the agreement.”

Template note: A template works best as structure, not as a script. Fill facts first, then confirm every item on the checklist is answered in plain language.

Secured vs Unsecured Personal Loans

Secured vs unsecured isn’t about making the document “more formal.” It’s about how the risk is handled if repayment doesn’t go as planned. An unsecured loan depends on crystal-clear terms and clean proof, while a secured personal loan agreement adds collateral rules that must be specific to be useful. For a plain-English explanation of what a “security interest” means in lending, see Cornell Law School’s LII definition of a security interest and collateral concept.

If you’re using a template, this is the section where “close enough” language causes the most problems later. The goal is simple: make repayment measurable, and make the consequences predictable.

Unsecured loan agreement (what must be crystal clear)

Schedule (make it measurable): Write exact due dates and exact amounts, and state whether payment counts when sent or when received. This is what keeps a simple unsecured loan agreement from turning into a vague promise. If it’s unclear, “late” becomes an argument (and a sample unsecured loan agreement won’t save you if the facts don’t match the wording).

Late rule (define “late”): Specify any grace period and the late fee (or “no late fee”). Clear late terms prevent emotional escalation because both sides know what happens next. If missing, enforcement can look arbitrary.

Default line (define the trigger): State what counts as default, whether there’s a cure period, and whether the balance can accelerate. Default terms create a predictable escalation path instead of improvisation. If vague, the borrower can dispute the lender’s next step.

Notices (make it provable): List notice addresses and accepted delivery methods for formal steps. Notice rules help prove the borrower was informed before consequences apply. If omitted, “I didn’t get it” becomes a common defense.

Proof (keep records): Keep proof of disbursement and each payment (bank confirmation, check image, or receipt). Proof prevents fights over what happened and keeps the agreement enforceable in practice. This matters even more when you start from an unsecured loan agreement template.

Secured personal loan agreement (collateral basics)

What collateral is (plain English): Collateral is an asset pledged to back the loan so the lender has an additional remedy if the borrower defaults. Collateral only helps if the asset is clearly identified and clearly tied to the debt. (State rules vary, but secured transactions in personal property are commonly handled under UCC Article 9 principles; the Uniform Law Commission summarizes that framework in its Uniform Commercial Code overview, including Article 9 secured transactions.)

How to describe collateral (make it identifiable): Describe the collateral using details that point to one specific item: VIN/serial number, make/model, condition if relevant, and where it is kept. A secured personal loan agreement template should force specificity, not categories. If you write “car” or “laptop” without identifiers, you invite disputes about what was pledged.

Release on payoff (how it gets cleared): Include a clear term that once the loan is paid in full, the lender will confirm the collateral is released and return any related documents. A release-on-payoff clause protects the borrower by preventing lingering claims after repayment. If you omit it, closing the loan can stay messy even when the money is fully repaid.

Risk trade-offs (lender vs borrower)

Unsecured loans are simpler and less intrusive, but the lender takes more risk and relies heavily on the schedule, default terms, and proof. Secured loans reduce lender risk and can make larger loans more realistic, but they raise the stakes for the borrower because default can put a specific asset at risk. The right choice is the one where both sides understand the consequences before funds are sent.

Mini checklist for secured add-ons (6–10 items)

Collateral description includes unique identifiers (VIN/serial/make/model), not generic labels

Location of collateral is stated, including whether it can be moved

Borrower agrees not to sell or re-pledge the collateral during the loan term

Maintenance/insurance responsibility is addressed where relevant

Default section clearly ties default triggers to collateral remedies

Notice requirement is stated before any collateral-related action

Release on payoff is stated (what the lender must provide and when)

Any attachments are listed if used (photos, receipts, detailed description page)

Types and Templates by Scenario

Templates aren’t one-size-fits-all. The fastest way to get a clean result is to identify your scenario first, then pick the closest starting document from the library, and only then customize the terms. A “good” template is the one that matches your risk profile (relationship, timeline, interest, collateral, co-signer), not the one that’s shortest.

Family loans (clarity + relationship risk)

A family loan agreement template works best when it removes “emotional ambiguity.” That means you should write terms that are simple to follow and hard to misread: a start date, exact due dates, and a clear statement on interest (or no interest). Family deals break down when both sides try to be “nice” and stay vague, because vague terms often become silent resentment.

If the loan is interest-free, say that plainly and keep records of disbursement and payments. If repayment is flexible, you can still make it measurable by using a schedule with the option to prepay or renegotiate in writing later. This is the core idea behind a loan agreement between family members: protect the relationship by removing guesswork.

Friends loans (boundaries + proof)

A personal loan agreement between friends should feel like a boundary tool, not a threat. The most important goal is a schedule everyone can live with and prove. Friends loans go sideways when payments become awkward to discuss, so the contract should do the talking: exact due dates, what happens if a payment is late, and where notices go if reminders don’t work.

Proof matters more than people expect. Even when nobody is acting in bad faith, memory fails. If you’re using a loan agreement between friends template, make sure payment method and record-keeping are not an afterthought — especially if any payments might be made in cash.

Unsecured installment loan

This is the common “monthly payments” deal: no collateral, but structured installments. The template should force you to define the schedule, late rules, and default triggers. Installment loans fail when the schedule is vague or when “late” isn’t defined, because the parties start renegotiating after every missed due date.

If you want it to stay simple, keep default language practical: define when a payment becomes late, whether there’s a grace period, and what the next step is if a payment is missed. If you later need to adjust dates, require a written amendment so the schedule doesn’t drift.

Secured loan (collateral)

Use a secured personal loan agreement when the amount is larger, the risk feels higher, or the lender needs extra comfort to lend at all. The key difference is collateral. Collateral is only real protection when it is described in a way that uniquely identifies the asset, not just a category.

In a secured template, spend more attention on the collateral section than any other part. Include identifying details (serial/VIN), location, and a clear release-on-payoff term. That last piece protects the borrower: it ensures the collateral is formally released once the loan is paid.

Interest-free loan

Interest-free loans are common in friends-and-family situations, but they still need a schedule and default rules. The core term is simple: “No interest will be charged.” The risk is that people assume an interest-free loan is also a “no deadlines” loan, which is where conflict begins.

An interest-free template works best when it feels like a repayment plan rather than a legal document. Focus on the due dates, payment method, and how to handle changes later in writing.

Demand loan (payable on demand)

A demand loan is repayable when the lender asks for payment, rather than on fixed installments. It can work for short-term, flexible arrangements where the borrower expects to repay quickly but the exact date is uncertain. The most important term in a demand loan is the demand mechanics, meaning how notice is delivered and how long the borrower has to pay after demand.

If you skip those mechanics, “on demand” can become a fight about what was reasonable. A good demand setup states the notice method and a clear payment window after the demand is received.

Promissory note scenario

Use a promissory note when you want something simpler than a full agreement, but still want a signed, clear promise to repay. This often fits loans with a single due date or a straightforward repayment plan and few extra protections. A promissory note works when the deal is simple enough that you don’t need a long “process” section.

If you’re choosing between a note and a full agreement, ask one question: do you need detailed rules for late payments, default steps, notices, and remedies? If yes, you’re usually back in full agreement territory.

Guarantor/co-signer scenario

A guarantor or co-signer scenario is appropriate when the lender wants additional assurance, or the borrower’s ability to repay is uncertain. The document needs to define scope: what exactly is guaranteed, when the guarantor can be pursued, and how the guarantor is released after payoff. Guarantee language should be explicit because vague scope creates the worst kind of surprise — unexpected liability.

Even if you start from a standard template, treat the guarantor section as a custom piece. Everyone should understand, in plain language, what the guarantor is on the hook for and when that responsibility ends.

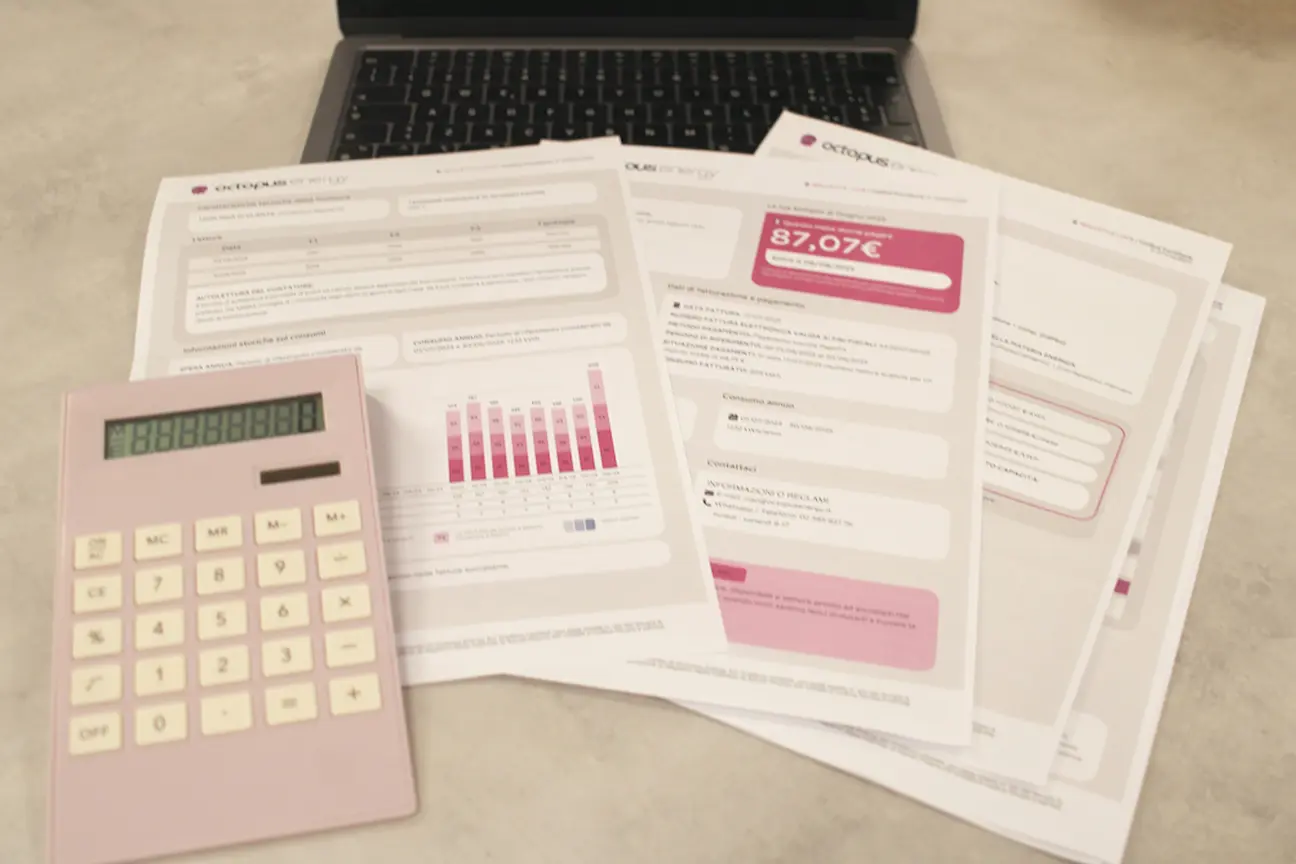

AI vs. Lawyer

There isn’t one “right” way to prepare a personal loan agreement. The best option depends on your risk level, how repeatable your lending is, and how rule-heavy the deal becomes (collateral, guarantor, multi-state facts, or a realistic conflict risk). Attorney pricing varies widely by state, experience, and complexity, so treat any numbers as directional. If you want a state-by-state benchmark view of typical hourly rates, Clio publishes aggregated data here: Clio’s lawyer rate benchmarks by state. ([Clio][1])

Option | Best for | Typical cost range (U.S.) | Main advantages | Main risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

DIY / AI (template + self-service) | Clear facts, low-to-mid stakes, single loan, simple unsecured terms you can document cleanly | $0–$50 (template) or ~$10–$60/mo (AI tool) | Fast to complete and easy to iterate, good for standard scenarios, keeps language plain | You can pick the wrong structure or leave gaps (unclear schedule, weak default steps, missing notice mechanics) that create confusion later |

Lawyer review (you draft, lawyer edits) | Mid-stakes, recurring friction risk, secured terms that need a check, co-signer language, or any “this might get messy” feeling | Often ~$200–$1,500+ for review time (varies) | Catches contradictions and state-sensitive issues without paying for full drafting, improves clarity and enforceability | Scope is limited; review may not include deep fact investigation or negotiation strategy |

Lawyer draft + strategy (attorney builds the package) | High stakes (large amounts), secured collateral with real downside, guarantor disputes, multi-state complexity, high conflict probability | Often $1,000–$5,000+ (flat or hourly; varies) | Stronger “what happens if…” terms, cleaner alignment across documents (loan, collateral, guaranty, releases), fewer loose ends | Higher cost and coordination; quality depends on complete facts and a clear workflow |

A practical rule is to use a template (and AI for clarity) when the facts are simple and the downside is manageable; pay for lawyer review when collateral, guarantees, multi-state issues, or conflict risk is real; and invest in full drafting when the agreement has to carry serious consequences if things go wrong.

Template Library

Templates are a great starting point, but they work best when you treat them like a matching tool, not an autopilot button. A solid personal loan agreement template is the one that fits your scenario and forces the deal facts into writing early (amount, dates, schedule, and what happens if a payment is late).

Use the library table below to pick the closest match to your situation. When the scenario matches, you spend less time editing and you avoid “template gaps” that create disputes later.

Category | Best for | Key fields to complete | Templates |

|---|---|---|---|

Family loans | Loans between relatives where clarity protects the relationship | Amount; disbursement; interest or no interest; schedule; late/default; amendments in writing; closeout terms (if forgiveness or payoff confirmation is needed) | |

Friends loans | Loans between friends where boundaries and proof matter | Amount; disbursement; schedule; payment method; proof expectations; late/default; notices | |

Unsecured installment loan | Monthly payments with no collateral | Installment schedule (dates/amounts); “paid when sent vs received”; grace/late fee; default/acceleration; notices; proof | |

Secured loan (collateral) | Loans backed by collateral | Collateral identifiers/location; default-to-collateral pathway; release on payoff; schedule; notices | |

Interest-free loan | Simple loans where the key variable is “no interest” | Principal; clear “no interest” statement; due date or simple schedule; payment method; signatures | |

Demand loan (payable on demand) | Flexible repayment triggered by a formal demand | Demand mechanics; deadline to pay after demand; delivery method; reference to underlying obligation | |

Promissory note scenario | A simpler promise-to-pay setup | Principal; interest/no-interest; due date or basic schedule; payment method; signatures | |

Guarantor/co-signer scenario | Loans that need a guarantor and a clean release | Guarantor scope; trigger for guarantor responsibility; notices; release conditions |

How to Use a Template Safely (Step-by-Step)

Templates save time, but a template only works when you treat it like a structured worksheet for your deal facts — not a one-click solution. Your goal is clarity that survives stress: numbers, dates, triggers, and proof. Use the steps below to fill the document, and use the Core structure checklist above as your final quality-control pass.

Step 1: Pick the closest scenario first (don’t draft “generic”)

Choose the template that matches your loan reality (family, friends, unsecured installments, secured collateral, interest-free, demand, promissory note, guarantor). The closest match prevents missing-term gaps because the document is already built to capture the clauses your scenario actually needs. If you start “generic,” you often end up patching terms later in a way that creates inconsistencies.

Checklist tie-in: Before you commit, scan the checklist items on schedule, default, notices, and collateral/guarantor. If your deal needs them, your template must include them.

Output: A selected template that matches your scenario, plus a clear reason why it fits your loan structure and risk level.

Step 2: Fill facts first (then stop and verify)

Fill the deal facts in one clean pass: full legal names, notice addresses, principal amount, funding date and method, and the intended timeline. Fact gaps are the fastest way to create a document that looks complete but fails later, because the “legal” language can’t compensate for missing dates, missing funding details, or unclear identities.

Checklist tie-in: Check off parties/notice addresses and loan amount/disbursement before you touch repayment mechanics.

Output: A complete deal-facts section where the parties, amount, funding method/date, and core dates are specific enough that a reader can understand the loan without guessing.

Step 3: Build the repayment schedule like a tracker, not a story

Write the repayment plan so it can be followed without interpretation: exact due dates, exact amounts, and a clear rule for what counts as paid (received vs sent). This is the part that turns the agreement into something you can actually run, and it’s also where vague language creates most disputes. If interest applies, make sure the schedule and interest wording don’t contradict each other.

Checklist tie-in: The schedule item is the centerpiece. If it isn’t measurable, the rest of the agreement won’t perform under stress.

Output: A repayment schedule with firm due dates and amounts, plus a clear “paid” definition, that can be pasted into the agreement and used to track compliance without debate.

Step 4: Add protections that match the risk, then check consistency

Now add the clauses that make the agreement function when something goes wrong: late-payment rules, default trigger, cure/notice steps, and notice delivery mechanics. Protections work only when they are objective and consistent with the schedule — late rules must match your due dates, default must specify what happens next, and notices must be provable. If the loan is secured, collateral must be uniquely identifiable and include a release-on-payoff term. If a guarantor is involved, scope and release conditions must be explicit.

Checklist tie-in: Cross-check late/default/notices against the schedule. If any section contradicts dates or amounts, fix that before signing.

Output: A final agreement where late rules are measurable, default triggers and remedies are clear, notice delivery is defined, and any collateral/guarantor add-ons are specific and consistent with the repayment plan.

Step 5: Sign cleanly and set up proof so the deal stays real

Finalize one version, sign it, store it in a single shared location, and set up a proof folder plus a payment ledger. The agreement stays enforceable in practice only if records are easy to produce: proof of disbursement, proof of each payment, and a running balance. If terms change later, document the change in writing and keep it with the original agreement so the schedule doesn’t drift into “we talked about it.”

Checklist tie-in: The signatures/attachments, proof, and amendments-in-writing items are what keep the agreement usable after real life happens.

Output: A signed final version stored in one place, plus a proof folder for funding/payment records and a payment ledger that is ready to update after every payment.

After Signing: Payment Tracking, Changes, and Closing the Loan

Signing is not the finish line. A personal loan contract only stays “real” if you track payments, document changes, and close the loan cleanly. Most disputes don’t start with bad intent; they start with missing records and fuzzy updates.

Set up a payment log (ledger)

Create one simple ledger the same day you sign, and update it after every payment. A payment log turns “I paid you” into a shared set of facts that both sides can verify.

A practical ledger format:

Date | Amount | Method | Memo / Reference | Remaining balance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Proof of payment (bank, check, cash)

Use payment methods that create a trail. Bank transfers and checks are easiest because they produce confirmations or images. Cash is the hardest method to prove, so it should only be used with a written receipt that both sides keep. If you must use cash, write the receipt like a mini-record: date, amount, purpose (“loan payment”), and remaining balance if possible.

Changing terms later (amendment in writing)

Life happens: a job loss, a delayed bonus, a medical bill. If the schedule changes, document it. A written amendment protects both sides because it prevents “we agreed verbally” arguments later. Keep it short: reference the original agreement, state what is changing (new dates/amounts), and have both parties sign and date it. Attach the updated schedule to the amendment and store it in the same folder as the original agreement.

If payments are late (soft reminders, then formal steps)

When a payment is late, use a predictable escalation path instead of improvising. A consistent workflow reduces conflict because it separates the relationship from the process. A common sequence looks like this:

Friendly reminder (a quick message with the missed due date and amount)

Written notice (restating the terms: what’s late, late fee if any, and the cure deadline)

A personal loan demand letter is a formal written step that sets a firm deadline to cure and is easier to prove later than texts and calls

Next steps under the agreement (acceleration if applicable, or other agreed remedies)

If the situation escalates to third-party collection, it’s smart to understand the basic rules that may apply; the CFPB’s overview of debt collection options and consumer protections is a helpful starting point.

When it’s paid off (loan satisfaction letter)

Once the balance is zero, close it out properly. A loan satisfaction letter is a simple confirmation that the debt is paid in full and no balance remains. It’s especially helpful for secured loans (to support collateral release) and for relationship loans (to prevent “do I still owe anything?” confusion later). Store it with the agreement and ledger.

If the lender forgives the loan (loan forgiveness agreement)

Sometimes repayment is waived. Do not leave that as an informal text. A loan forgiveness agreement documents that the lender is intentionally canceling the debt and the borrower no longer owes it. Also remember that forgiveness can have tax implications depending on the facts, so it’s worth reviewing IRS guidance on canceled debt basics before you treat the matter as fully closed.

Guarantees (release of personal guarantee)

If a guarantor/co-signer was involved, close that loop too. A release of personal guarantee is the clean way to end the guarantor’s liability once the loan is satisfied (or if the lender agrees to release them earlier). Keep it consistent with the guarantor agreement and the final payoff confirmation so there’s no mismatch about what is still owed and who is still responsible.

Legal Requirements and Regulatory Context (U.S.)

A personal loan agreement in the U.S. is mostly contract law plus state-specific rules that can change the details (especially interest limits and secured collateral steps). Most “legal” disputes happen because terms are unclear or records are missing, not because the document wasn’t “legal enough.” The safest drafting mindset is to make every key term measurable and provable (numbers, dates, triggers, and receipts).

Contract enforceability basics (what makes it “stick”)

At a high level, an agreement is easier to enforce when it shows clear assent and clear terms. Cornell LII provides plain-English refreshers on consideration and contractual capacity. In practice, enforceability often turns on whether a neutral reader can tell what was promised and when. If repayment timing is vague, interest is implied instead of written, or the schedule can’t be reconstructed from records, disputes become much easier to argue.

Disputes can also include “how it was signed” defenses. Cornell LII explains duress and unconscionability. Clean drafting plus clean documentation reduces the room for these defenses because it shows intent, clarity, and consistency.

Statute of frauds (when writing matters more)

Some promises must be in writing under a state’s statute of frauds, and the categories vary. Cornell LII’s overview is here: statute of frauds. Even when a verbal deal might be enforceable in theory, a signed writing usually prevents the real problem: “we remember it differently.”

E-signatures and record retention

E-signing is common, and federal law generally supports it. The E-SIGN Act’s core rule is in the statute text: 15 U.S.C. § 7001 on govinfo. The practical requirement is record quality: you should be able to keep and reproduce an accurate final signed copy (often a PDF), not just a chain of emails and drafts.

Interest and “below-market” context

Interest rules and maximum rates are largely state-driven, so be careful with copied clauses. For family or interest-free loans, it can be helpful to know the federal benchmark rates used in certain tax contexts; see the IRS Applicable Federal Rates (AFR). If lending becomes frequent or business-like, disclosure frameworks may matter more, and you can review the Truth in Lending regulation text at eCFR: 12 CFR Part 1026 (Regulation Z).

Secured loans and collateral formalities

If the loan is secured, the agreement must identify collateral precisely and define release on payoff. Cornell LII’s secured transactions overview is a helpful starting point. “Secured” only helps when the collateral terms are specific enough to operate in practice and consistent with the rest of the agreement.

Collection and debt collection rules

If the loan goes into serious delinquency, and especially if third parties get involved, debt collection rules may matter. The official resource is the FTC FDCPA statute page, and the implementing regulation is available at eCFR: 12 CFR Part 1006 (Regulation F). Even when those rules don’t squarely apply, a documented, notice-based process makes escalation more defensible and easier to prove.

Common Mistakes to Avoid (Expanded)

Most issues with a personal loan agreement aren’t “legal technicalities.” They happen because the document is vague where it must be specific, or because the parties rely on memory instead of records. A practical loan agreement sample prevents expensive misunderstandings by forcing the sensitive terms into writing early — before a missed payment turns into a relationship problem.

1) Choosing the wrong document type (IOU vs note vs agreement)

People often start with the shortest option and hope it “counts.” But the wrong document type usually fails at the exact moment you need it most — when a payment is late and you need clear next steps.

Fix it: Use a full loan agreement when you need a schedule, late fees, default steps, notices, collateral, or a co-signer. Use a promissory note only when the terms are truly simple and you don’t need a detailed process.

2) Writing a schedule that isn’t measurable

“Monthly payments” without exact dates and amounts sounds friendly, but it’s not a plan. If the schedule can’t be checked like a calendar, it becomes a negotiation every month.

Fix it: List exact due dates and exact amounts. If you want flexibility, keep the schedule firm and allow changes only through a written amendment.

3) Leaving interest terms implied or inconsistent

Interest is where assumptions multiply: “I thought it was interest-free” versus “I assumed you’d pay something for the time.” When interest isn’t written clearly, payoff math becomes a dispute instead of a calculation.

Fix it: State the interest rate and how it accrues, or write a clear “no interest” sentence. Make sure the schedule aligns with the interest approach.

4) Not defining what “late” means (and what the late fee rule is)

A late fee clause without a clear trigger is a common template gap. If lateness isn’t defined, enforcement feels arbitrary and personal.

Fix it: Define when a payment becomes late (including any grace period) and the late fee amount (or “no late fee”).

5) Missing default triggers and what happens after default

Many “simple loan agreement” drafts talk about repayment but never define default. Without default language, escalation becomes improvised — and easier to challenge later.

Fix it: Define default, any cure period, required notice, and whether the lender can accelerate the remaining balance (or explicitly say there is no acceleration).

6) Calling it “secured” but describing collateral poorly

Collateral only helps if it’s actually identifiable. A vague collateral description can make a “secured” deal function like an unsecured one in practice.

Fix it: Describe collateral with identifiers (VIN/serial/make/model), location, and condition if relevant. Include a clear release-on-payoff term.

7) Failing to keep proof of disbursement and payments

Even when both sides are honest, memory fades. Weak proof turns a factual timeline into a “he said / she said” conflict.

Fix it: Save proof of funding (transfer confirmation/check image) and proof of each payment. Avoid cash; if cash is used, always use a signed receipt.

8) Allowing informal changes without documenting them

Friends-and-family loans often shift when life happens, then nobody is sure what the “new deal” is. Verbal changes create drifting obligations that are hard to enforce and hard to track.

Fix it: Add a “changes must be in writing and signed” clause, and attach the updated repayment schedule to the amendment.

FAQ: Personal Loan Agreement

Q: What is a personal loan agreement?

A: A personal loan agreement is a written contract that documents a private loan between individuals. In plain English, it turns “I’ll pay you back” into a clear, checkable record: how much was loaned, when payments are due, whether interest applies, and what happens if payments are late.

Q: Why do I need a personal loan agreement?

A: You need one when money and relationships overlap, or when repayment will happen over time. A written agreement prevents “we remembered it differently” disputes by locking in the schedule, proof expectations, and next steps if something goes wrong.

Q: What should a personal loan agreement include?

A: At minimum, it should include the parties’ names and notice info, the amount, how funds are delivered, interest or no interest, a repayment schedule, payment method, late rules, default triggers, and signatures. If any of those are missing, the loan becomes harder to track and harder to enforce when there’s friction.

Q: How do I write a personal loan agreement?

A: Start with the closest template for your scenario, then fill the deal facts first (names, amount, disbursement, dates). Next, build a repayment schedule with exact due dates and amounts, and add clear late/default and notice mechanics. If a stranger couldn’t follow the schedule without guessing, the agreement isn’t finished yet.

Q: What’s the difference between a personal loan agreement and a simple loan agreement?

A: A “simple” loan agreement usually keeps the same core terms but uses fewer optional clauses and less detail. The practical difference is not the label — it’s whether the document covers the friction points (late payments, default steps, notices, and proof) in a way you can actually use.

Q: When should I use a secured vs. an unsecured loan agreement?

A: Use an unsecured agreement when no collateral backs the loan and you’re relying on the borrower’s promise. Use a secured agreement when collateral is pledged and losing that collateral is an acceptable consequence of default. Secured loans require precise collateral identification and clear release-on-payoff terms or they won’t function as intended.

Q: Can I use a personal loan agreement template for family loans?

A: Yes. In family situations, the template’s job is to reduce emotional ambiguity. A family loan agreement works best when the “no interest” or interest terms and the repayment schedule are unmistakably clear and changes require a written amendment.

Q: Can I use a personal loan agreement for loans between friends?

A: Yes, and it often helps more than people expect. A friends loan agreement is primarily a boundaries-and-proof tool: it keeps the schedule clear, makes payments trackable, and reduces awkward conversations by letting the document do the explaining.

Q: What terms should I set for interest, late fees, and repayment schedule?

A: Set terms that are measurable and realistic: interest should be clearly stated (or clearly waived), late fees should have a clear trigger and grace period (or be explicitly “none”), and the schedule should list exact due dates and exact amounts. The best terms are the ones you can track without interpretation and enforce without improvisation.

Q: What’s the difference between a promissory note and a loan agreement?

A: A promissory note is a written promise to repay — often shorter and more focused on the principal, interest, and due date. A loan agreement is broader and typically includes process terms like late fees, default steps, notices, and remedies. If you need clear “what happens if” rules, a loan agreement is usually the better fit.

Get Started Today

A strong personal loan agreement protects your money, your timeline, and your relationships. When the key terms are written down, repayment stops being a “memory-based” promise and becomes a plan you can actually follow: amount, dates, schedule, late/default rules, and proof.

Use the scenario section above to choose the closest starting point (family, friends, unsecured installments, secured collateral, interest-free, demand, promissory note, or guarantor). Then pair it with a simple tracking routine so the agreement stays real after signing: keep a payment ledger, save proof of disbursement and each payment, and document any changes in writing instead of “verbal updates.”

Start with the Personal Loan Agreement Template from our library, or generate a first draft with AI Lawyer and then customize it to your deal points (amount, repayment schedule, interest or no interest, late fees, default steps, and any collateral or guarantor add-ons). If the stakes are high — large dollar amounts, collateral, co-signers, or multi-state issues — consider having a U.S. lawyer review the agreement before you sign.

You Might Also Like:

Sources and References

Core contract framing in this guide (what makes a personal loan agreement enforceable in principle, and why wording and specificity matter) draws on Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute overview of contracts and related contract basics.

Discussion of when “put it in writing” matters (and why some agreements are treated as writing-sensitive) follows the general concept explained in Cornell LII’s overview of the statute of frauds, which is a useful orientation for when written terms and signatures become especially important.

Electronic signature and record-validity references rely on the federal E-SIGN framework, as summarized in the statutory text of 15 U.S.C. § 7001 (Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act).

Interest-rate and “below-market” loan context (especially relevant to friends-and-family loans) is informed by the IRS’s benchmark rate guidance, including the IRS Applicable Federal Rates (AFR) page.

Lending disclosure and “repeatable lending” context references use the Truth in Lending framework as implemented in Regulation Z, including the eCFR text for 12 CFR Part 1026 (Regulation Z).

Debt-collection escalation awareness (especially when third parties become involved) references the federal statute and implementing regulation, including the FTC’s FDCPA statute page and the eCFR text for 12 CFR Part 1006 (Regulation F).