AI Lawyer Blog

Local Criminal Lawyer Near Me: What San Francisco’s January 2026 Defense Crisis Reveals About Showing Up With Counsel

Greg Mitchell | Legal consultant at AI Lawyer

3

A criminal case can start before you’ve even had time to understand what you’re accused of. One missed phone call, one rushed first appearance, one “I’ll explain” to the wrong person — and suddenly the story of your case is being written without you holding the pen. That’s why the San Francisco defense breakdown in January 2026 matters: it exposed what people learn the hard way in counties across the U.S. — the right to a lawyer can exist on paper while access fails at the exact moment the court keeps moving. The constitutional promise is real (see the National Archives overview of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel), but the practical reality depends on whether a lawyer can actually show up, prepare, and act fast.

This guide is a practical, U.S.-focused walkthrough for anyone searching in a panic after an arrest, a surprise warrant, or a first hearing date. “Local” isn’t a marketing adjective — it’s what determines how fast someone can appear, how well they know the courthouse, and whether early decisions get handled before they harden into conditions and deadlines. You’ll learn how public defenders, conflict counsel, and private attorneys fit together when the system is overloaded, and what to do in the first 24–72 hours to protect your options. A good plan turns chaos into steps: who to call, what to say, what not to say, what to gather, and how to avoid early mistakes that are hard to undo.

Disclaimer

This article provides general information — not legal advice — and it is written for a U.S. audience. Criminal cases can move quickly, and the rules and local courtroom practices that matter most early on (arraignment timing, bail arguments, release conditions, and no-contact orders) can differ by state, county, and even by judge. Because the first 24–72 hours after an arrest or a first hearing can affect custody status, protective orders, what evidence gets preserved, and what you say on the record, speaking with a qualified criminal defense attorney licensed in the jurisdiction handling your case can help you avoid early mistakes that are difficult to fix later — especially in felony matters or cases involving alleged violence, weapons, drugs, or any restriction on contact with another person.

TL;DR

Early hearings can shape your case immediately. Bail, release conditions, and protective orders can be set before you feel “ready,” so the first appearance matters.

The San Francisco crisis showed how representation can break at the worst time. Even when the right to counsel exists, staffing and appointment systems can lag behind the court calendar.

A lawyer’s “local” value is practical, not cosmetic. Court familiarity, speed to appear, and knowing the prosecutor/judge routines often matter more than a polished website.

Silence is usually safer than explanations. Anything you say to police, in recorded jail calls, or on the courthouse record can become evidence later.

The first 24–72 hours are about preventing damage and preserving options. Identify witnesses, save messages/videos, document timelines, and avoid contact that could violate conditions.

If a public defender can’t take the case right away, alternatives may exist. Conflict/panel counsel and private defense can fill gaps when the standard appointment pipeline stalls.

You Might Also Like:

What Happened in San Francisco in January 2026: “Take the Cases or Face Contempt”

San Francisco hit a problem that sounds impossible until you see it up close: people were getting felony charges, the court calendar kept moving, and the usual pipeline for assigning defense counsel started to crack. The Public Defender’s Office said it didn’t have enough capacity to keep accepting some new felony appointments. The court saw the downstream effect immediately — defendants showing up at early hearings without a lawyer, or with representation uncertain at the moment decisions were being made.

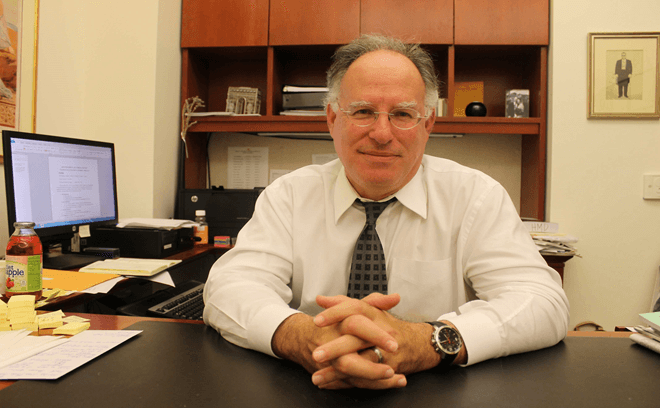

Judge Harry Dorfman’s response wasn’t just political — it was procedural. He signaled that the court could not run an arraignment docket where felony cases routinely appear without counsel, and he pressed the Public Defender’s Office to resume taking felony appointments except in clear conflict-of-interest situations. When a court frames the issue as compliance with appointment orders, “resource crisis” stops being a headline and becomes a courtroom deadline. That’s where the contempt threat enters: contempt is the judge’s tool for enforcing the court’s authority when an order is ignored. As Cornell’s Legal Information Institute explains, “Contempt of court” involves “disobedience” or “disrespect” toward the court’s authority (see Cornell LII’s overview of contempt of court in plain language). In this context, contempt wasn’t about drama — it was leverage to keep the system functioning.

The Public Defender’s counterpoint was equally concrete: taking more cases than the office can responsibly handle risks turning representation into a formality — lawyer on paper, not protection in practice. A defense lawyer’s ethical duty isn’t just to “be assigned,” but to provide competent, real advocacy — especially at the beginning, when conditions and strategy get set. That’s why this dispute matters to anyone searching for local criminal attorneys or a local criminal defense attorney: it reveals how quickly “I’ll get a lawyer” can collide with the reality of who can actually show up and prepare.

If you’ve never been through the system, the vocabulary can hide what’s happening. “Arraignment” is typically the first court appearance where charges are read and key conditions may be set; the U.S. federal courts describe the broader sequence in their overview of the criminal justice process. When representation wobbles at arraignment, the consequences can start before the case has any real factual investigation behind it. And when the public system is strained, the burden often shifts outward — onto conflict counsel, panel appointments, and private local defense attorneys who can move faster than the overloaded pipeline.

The “Local Hero” Is an Ecosystem: Public Defender, Conflict Counsel, and Private Firms

In real courtrooms, “local” defense is rarely one person. It’s a coverage network designed to keep cases from turning into “defendant versus the calendar.” The first layer is usually the public defender: the office built to appear early, handle volume, and keep arraignments from becoming one-way decisions. But that model depends on capacity. When felony filings surge or staffing can’t keep pace, the system starts to wobble exactly where timing matters most — at the first appearance, when rules for your life can be set in minutes.

When the public defender cannot take a case, the system doesn’t stop — it reroutes. The second layer is conflict counsel (often court-appointed private attorneys). “Conflict” sounds personal, but it’s usually structural: co-defendants, key witnesses, or overlapping matters can make it unethical for the same office to represent everyone. That’s the point of conflict appointments: to keep representation clean and loyal, not divided. In San Francisco, this handoff is supported by local appointment programs described by the Bar Association of San Francisco’s Indigent Defense Administration, which helps coordinate counsel when the public defender can’t represent someone. When the main office is strained, this panel system can become the emergency valve that prevents people from standing alone at counsel table.

Private criminal defense firms sit alongside — and sometimes within — this network. Some families retain private counsel immediately because they need speed, focused attention, or a lawyer who already knows the courthouse routines and can appear fast. Others look private only after they run into delays, overload, or uncertainty in the appointment pipeline. Either way, the practical difference isn’t “public versus private” as a label — it’s whether someone can engage early, preserve evidence, and respond before the court locks in conditions that take weeks to unwind.

The bottom line is simple: “local” means someone can actually show up and do real work fast — because early hearings set bail, restrictions, and next steps that can shape the entire case before any deeper investigation begins.

The Legal Fight: The State’s Duty Versus Ethics and Real Capacity

From the court’s perspective, the problem is immediate: hearings still happen, deadlines still run, and people’s liberty can turn on what is argued in the first appearance. If a felony calendar starts moving without defense counsel at the table, the process can tilt fast — through bail decisions, release conditions, and restrictions that begin applying right away. Judges also have to keep the courtroom functioning, which is why San Francisco’s dispute escalated from a staffing issue into an enforcement issue.

From the defense side, the problem is just as concrete. A lawyer is not allowed to take on more work than they can handle competently. That isn’t a technicality — it’s the difference between real advocacy and a name on a docket. In overload conditions, representation can become delayed, rushed, or purely formal, and early-stage mistakes can be hard to undo later. California’s professional rules emphasize competence and the duties owed to clients (see the State Bar of California’s Rules of Professional Conduct), which makes “we can’t take more cases” an ethical argument as much as an operational one.

The key takeaway is that the constitutional promise and the staffing reality can collide at the worst moment — so the practical goal is not just getting “assigned” counsel, but getting counsel who can act before early decisions harden into long-term consequences.

What This Changes for Someone Googling “Near Me” After an Arrest

If you’re searching “local criminal lawyers near me” late at night or between court dates, you’re not behind. You’re reacting to the real pace of the system.

The San Francisco crisis highlighted a hard truth: court can reach the “next step” before the defense pipeline catches up. Your first problem is often not the trial. It’s what gets decided before trial is even on the horizon.

Why the first 24–72 hours matter

Most people think the case “starts” when a lawyer has time to dig in. In practice, the case starts the moment you’re arrested or told you must appear.

Bail and release conditions can be set before your side has gathered facts. If no one pushes back, you may face higher bail, stricter supervision, or custody time that pressures later decisions.

Protective orders and no-contact rules can appear early. In alleged violence, threats, or domestic situations, courts may impose restrictions fast, and violations can trigger new charges or revoke release.

Statements happen before strategy. Police questioning, recorded jail calls, and even texts can become evidence long before you understand what the state claims it has.

Evidence disappears quickly. Video overwrites, phones get wiped, witnesses scatter, and memories fade. Those first days are often your best chance to preserve details.

Mini-checklist: the first 60 minutes after an arrest, or before arraignment

Say you want a lawyer and stop answering questions.

Avoid “explaining” to fill silence.

Assume jail calls are recorded and monitored.

Write down your timeline while it’s fresh.

Identify evidence that could vanish (video, messages, logs).

List witnesses and save reliable contact info.

If you have court, arrive early and take it seriously.

Call a lawyer for speed and courtroom familiarity, not a sales pitch.

What “local” really means under time pressure

“Local” is not a nice-to-have. It’s operational.

A truly local lawyer can often appear fast and move inside that courthouse’s routines. They may know what arguments land, what bail options are realistic, and how that department typically handles conditions.

When the public system is overloaded, that timing advantage becomes the difference between reacting and shaping the outcome.

A short example that happens all the time

Someone is arrested on a felony allegation late Friday. The first appearance is Monday morning.

No lawyer meets them beforehand. A temporary protective order is entered “just in case.” A no-contact condition is added to release.

They call home from jail to “explain,” not realizing the call is recorded. Family members try to “clear things up” by contacting the other person. Now there’s a reported violation.

Within 72 hours, the case has extra problems created by timing and missteps, not just the original allegation.

That’s the practical takeaway from San Francisco: early stages are where damage happens quickly, and the right help is the help that can engage immediately.

How to Choose a Local Criminal Lawyer Without Wasting the First 24 Hours

In the first day, the goal isn’t to find the flashiest profile — it’s to find someone who can step into your courthouse quickly and make smart early moves. Felony exposure, alleged violence, weapons, drugs, or a protective-order risk all raise the cost of delay, because bail arguments and release conditions can be set before anyone has time to “catch up.”

A quick way to filter is to listen for testable, time-based answers. Can they appear at the next hearing? How soon can they speak to the client? Do they regularly practice in that courthouse? Who will actually do the work day-to-day? If the answers stay vague or turn into guarantees, treat that as a signal that you may not get real early engagement when you need it most.

The takeaway is to choose the lawyer who can explain the next 72 hours in clear steps and can realistically act before the next hearing — not the lawyer who simply sounds confident on the phone.

Common Mistakes When No Lawyer Is Beside You

When you don’t have counsel next to you, most harm comes from “normal” behavior — trying to explain, trying to be helpful, trying to calm the situation. Police questions, casual texts, and even courthouse small talk can turn into evidence, and you usually don’t know what the state thinks it has yet. The urge to talk is human, but early statements can lock you into a version of events before you understand the stakes.

The other big cluster of mistakes is avoidable violations. Jail calls are often recorded. Social posts can be screenshotted. And no-contact or stay-away conditions — especially in cases involving alleged violence — can be broken accidentally through a “third-party message” or “just checking in.” Missing a hearing is also catastrophic: it can trigger a bench warrant and make release harder later.

The takeaway is that your safest early moves are boring: say you want a lawyer, stop discussing the facts, don’t contact involved parties, and don’t create new violations while you’re trying to solve the original problem.

Legal Requirements and Regulatory Context

In the U.S., the baseline rule is that a person facing criminal charges has a right to counsel, and courts are expected to make that right real early in the process — not only at trial. The National Archives text of the Sixth Amendment is the core reference point, and it’s why courts take the “no lawyer at the first appearance” problem seriously.

At the same time, the system runs on procedures and timelines that don’t automatically pause when representation is delayed. Early appearances can set bail and release conditions, and courts rely on structured rules to move cases forward (see the U.S. Courts overview of the criminal case process). Lawyers also have ethical duties — especially competence and adequate preparation — so overload can create real tension between “being assigned” and “being effective.”

The practical takeaway is that the law assumes counsel shows up early, but your job is to make sure someone can actually act before the first hearing locks in conditions that can shape the rest of the case.

A Human Ending: Why This Case Is a Warning for the Whole System

After the hearing, the hallway clears in waves. Families step outside with paperwork they barely understand — dates, conditions, warnings — while the courthouse keeps calling the next name. In January 2026, San Francisco’s clash made something visible that usually stays hidden: the system can keep moving even when the defense side is short-staffed, and that gap shows up first at the earliest, most time-sensitive moments.

That’s why people end up on their phones, searching for help that can actually appear and act. It’s not about “upgrading” the Constitution; it’s about preventing the case from moving forward without anyone steering — especially when bail, no-contact rules, and other restrictions can be imposed before real defense work begins.

The takeaway is simple: the court calendar doesn’t wait, so early representation isn’t a luxury — it’s the difference between reacting to conditions later and shaping them before they harden.

FAQ

Q: How fast can a local criminal defense attorney appear in court?

A: It depends on the court schedule and whether the lawyer is already practicing in that courthouse, but speed usually comes down to logistics: how quickly they can confirm the next hearing, file a notice of appearance, and get access to the basic case information. “Local” matters most when it reduces delay between the arrest and the first meaningful advocacy. If the next hearing is within 24–72 hours, tell the lawyer that timeline immediately.

Q: What if I show up in court without a lawyer?

A: You can still be called and processed through arraignment steps, including bail and release conditions. Some judges will continue the case briefly to allow counsel to be appointed, but the court may still set dates and impose conditions. Going alone increases the risk that early decisions get made without anyone pushing back or explaining consequences. If you must appear, show up, say you want counsel, and avoid discussing facts on the record.

Q: A public defender refused my case or said they can’t take it yet — what now?

A: In many places, a refusal is tied to conflicts, capacity, or appointment logistics, not a judgment about you. Courts can appoint conflict counsel when the public defender cannot ethically represent you, and some jurisdictions use panel programs to assign attorneys. If the appointment pipeline is delayed, the urgent question becomes who can intervene before the next hearing. That may include court-appointed panel counsel or private counsel, depending on your situation.

Q: How do I find local criminal lawyers near me tonight or on a weekend?

A: Focus on lawyers who advertise emergency availability and who actually practice in the courthouse handling your case. When you call, lead with your next court date, custody status, and the charge level (misdemeanor vs felony), and ask whether they can appear. A fast “yes” means little if the lawyer cannot realistically attend the next hearing or speak to the client promptly. If you can’t reach anyone, keep calling and document who you contacted.

Q: Should my family call the alleged victim or complainant to “fix it”?

A: Usually no. Contact can violate no-contact conditions even if you think no order exists yet, and it can create new allegations like witness intimidation or harassment. Well-meant outreach is one of the quickest ways families accidentally make a case worse. Keep communication routed through counsel once you have it.

Q: Are jail phone calls really recorded, and can they be used in court?

A: Often, yes. Many facilities record calls and announce it at the start, and prosecutors can seek those recordings. A “private” explanation to family can become evidence that locks in a timeline or admissions. Avoid discussing facts, witnesses, or messages on any monitored line.

Q: What should I do in the first 24 hours to help my defense without making things worse?

A: Preserve information instead of arguing the case. Write a timeline, list witnesses, save messages and videos, and gather documents that support release (work, school, medical needs). The safest early goal is to protect options and prevent avoidable violations, not to “win the narrative” immediately.

Get Started Today

A strong defense plan protects your time, your freedom, and your leverage. When the next steps are clear, the risks are identified, and responsibilities are organized, you reduce “panic decisions” and move faster toward a stable outcome.

Use the sections above to identify where your case is right now (arrest, warrant, first hearing, bail, protective order), then pair that clarity with a simple 24–72 hour action plan so the system can’t lock in damaging conditions before your side is ready. A clear plan plus a fast first appearance turns crisis into a trackable process instead of scattered calls and guesswork.

If you’re trying to get organized fast, AI Lawyer can help you turn panic into a checklist: draft a call script, summarize the timeline you remember, and generate a first-pass set of questions for your attorney based on your charge type and court stage. If the stakes are high — felony exposure, alleged violence, weapons, drugs, immigration risk, or no-contact conditions — consider having a U.S.-licensed criminal defense lawyer review your situation before you make statements, sign anything, or contact anyone involved.

You Might Also Like:

Sources and References

For the official “ground truth” on how San Francisco’s defense system is supposed to function, start with the San Francisco Public Defender’s official site and the San Francisco Superior Court Criminal Division overview. If you need to confirm basic case visibility or look up a file number, the court’s case information lookup page is the safest starting point. These primary sources explain what the system is designed to do, even when staffing reality lags behind.

For the court-order standoff in January 2026, see the San Francisco Chronicle report on Dorfman’s mandate that the PD accept new felony cases absent conflicts (Chronicle coverage of the judicial order and defense crisis) and the Daily Journal write-up on the contempt posture (Daily Journal reporting on the contempt threat and felony intake refusal). For context on overflow pressure on local criminal lawyers outside the PD, read Mission Local on private counsel acting as a “second office” (Mission Local on private attorneys absorbing indigent defense overflow).